http://www.thestar.com/Business/article/719544

The Star

Selling trust in democracy

November 02, 2009

Iain Marlow

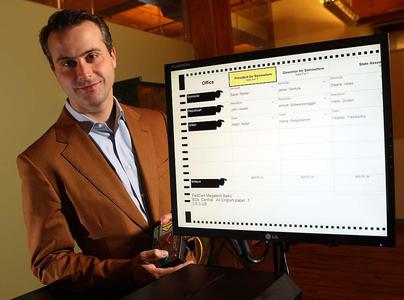

Electrical engineer and entrepreneur John Poulos displays technology Dominion Voting Systems Corp. developed in Toronto that will be used in the 2010 Philippines national elections. "They're trying to improve their accuracy and provide a level of transparency that our machines afford them." RENÉ JOHNSTON/TORONTO STAR

It's a cliché on the Left that democracy is big business,

that this particularly complicated political system is ripe with opportunities

for boundless profiteering.

For John Poulos, whose firm sells equipment that helps

governments run technologically advanced elections, it's not quite that simple

– the link between a cast vote and a quick buck not quite that seamless.

"It's a struggle," he says.

Customers are budget-conscious and hesitant to change,

Poulos explains, often using technology bought 50 or more years ago.

Yet, in the past five years, his Toronto-based firm has

posted a remarkable growth rate of 10,356 per cent. This is a rather grand way

of saying Dominion Voting Systems Corp. grew from four men and an idea to about

95 employees and a customizable product – enough to earn Dominion Voting No. 2

spot on Deloitte's 2009 list of the 50 fastest-growing Canadian tech firms.

It does not trade publicly and, on election days, those who

cast ballots may not think twice about the machine tabulating their votes.

But if you recently cast a municipal vote in Oakville,

Pickering or Montreal, or a provincial vote in September 's St. Paul's

by-election – or were among the many in the state of New York who voted for

senator Barack Obama for U.S. president – you may have used the handiwork of

this relatively small Canadian company.

Those who remember Florida's "hanging chad" fiasco

of 2000 and its stain on American democracy know just how important the

technology behind elections really is. The pace of technological change among

potential clients is practically glacial, but Dominion has thrived. It has few

rivals but has run test trials in the U.K. and Colombia and is contributing

voting technology to the Philippines' 2010 national election.

Poulos started Dominion Voting in 2002, after the disaster

in Florida. Tens of thousands of incorrectly punched ballots were discounted,

leading to accusations of fraud in the tight race between George W. Bush and

Democrat Al Gore. "There was ... quite a bit of money spent a few years

ago" on electronic voting machines, touted as more reliable, says Richard

Niemi, a professor at the University of Rochester who researches voting

machines and ballot design.

In New York state, Dominion's technology is replacing

50-year-old, 363-kilogram clunkers

Dominion's system mixes electronics and paper, combining an

analog paper trail of each person's vote with the advantages of quick, digital

tallying. Its optical scanning technology is widely respected but American

clients, at least post-Florida, looked on Dominion's use of paper as quaint.

"That was not seen as sexy," Poulos says.

What happened in a Sarasota County election in 2006 swung

opinion the other way: an electronic undercount effectively denied 18,000

citizens their right to vote.

"That's a huge travesty of democracy," says Renan

Levine, a political scientist at the University of Toronto, noting purely digital

voting machines can be wiped clean. "If you've got a crash in the middle

of the day, what are you going to do? Call those people back to vote?"

It reminded everyone that a paper trail is a good backup.

"The general feeling now is that people want paper,"

Niemi says.

Vote-fixing is extremely difficult on Dominion's machines,

Poulos adds, because tampered-with computer hard drives will not send votes to

the central tally.

Most importantly under Dominion's current strategy,

technological developments have ensured that those with disabilities can cast

secure votes, without help.

Sitting in his sun-drenched office on Spadina Ave., the

electrical engineer with an MBA, turned entrepreneur, says, . . "We are

profitable. People know where to find us."

He prefers to speak

about democracy as it exists in the world. Mail votes in Oregon. Electronic

voting in India and Brazil. Paper ballots counted by hand in Canada's national

elections. Where electorates could tear down capitals if fraud is suspected, voting

technology can act to legitimize sometimes shaky democracy.

"Perception is everything," Poulos adds.

"People can just say, `That machine is broken. I don't trust it'."

He says his machines are open to multi-party scrutiny. That

serves democracy.

Dominion's ballot-box scanning technology will be deployed

across the Philippines. "They're trying to improve their accuracy and

provide a level of transparency that our machines afford them," he

explains. "Maybe, in the second or third election," Manila will add

Dominion's accessibility technology so all can cast a ballot independently.

Maybe, indeed.