http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/03/10/a-love-affair-with-lever-voting-machines/

The New York Times

N.Y./Region, City Room - Blogging From the Five Boroughs

March 10, 2009, 7:15 am

A Love Affair With Lever Voting Machines

By Jennifer 8. Lee

Michael

Appleton for The New York Times

Three

counties have passed resolutions in support of keeping the lever voting

machines in New York State, despite federal and state legislation that require

upgrades.

As skepticism grows over computerized voting systems nationwide, a growing push is emerging in New York State to keep the once-disdained lever voting machines around. The proponents argue that given the financial crisis, now is not the time to be spending millions of dollars on upgrading decades-old machines that are actually more reliable than the new systems out there.

They prefer the clunky old relics, thank you (despite the occasional jam).

In the last several weeks, three counties — Dutchess, Ulster and Columbia — and the Association of Towns have passed resolutions urging the New York State government to enact laws allowing the lever machines to stay. In addition, the city’s Board of Elections held a hearing last week to hear lever supporters make their case for keeping the machines in New York.

“We’re where lever machines were born, and if I have my way, it’s not where they are going to die,” said Andrea Novick, founder of the Election Transparency Coalition, who has been litigating on this issue.

The push comes now in large part because accessible machines for impaired voters were installed at each poll site for the 2008 election. Lever proponents argue that these new machines bring New York into compliance with the federal voting reform legislation, passed after the 2000

recount debacle, which is called the Help America Vote Act of 2002. The machines, despite their aged technology and flaws, are more transparent and reliable than the so-called black box

Alejandra Laviada for The

New York Times

Alejandra Laviada for The

New York Times

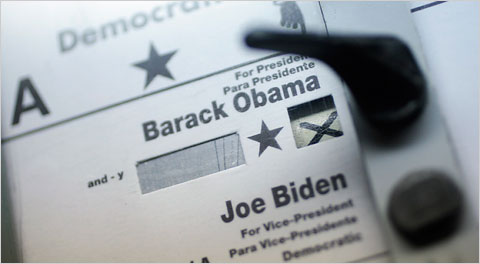

Lever

voting machines may look obsolete, but they are actually very reliable, their

proponents say.

systems, their proponents argue. (Others have a different opinion.) Lever machines work by incrementing counters in the back each time a voter pulls the lever. At the end of the day, the machines are opened in public and the counts are tallied, though some people criticize this as being opaque and lacking a paper trail).

New York has long been a laggard in complying with voting reform, to the point that the Department of Justice took legal action against the state in 2006 because it was further behind “than any other state in the country.”

Now, given all the problems that have emerged in other states, local election officials are publicly relieved that they have not wasted tens of millions of dollars in installing systems that just had to be uninstalled. However, New York’s Election Reform and Modernization Act of 2005 (which is more strict than the federal legislation) would seem to ban lever voting machines because they do not create a paper audit trail (as opposed to the entire voting site having an audit trail).

But New York has taken a somewhat passive-aggressive stance on upgrading the machines. By delaying, they keep the lever machines around. For example. it is too late to install anything new for the 2009 elections. “The transition to a new voting system at this point in the voting cycle jeopardizes the election itself,” said Gregory Somas, a commissioner of the Board of Elections in New York City.

Proponents of the lever machines — and there are many — say they should not be underestimated. Despite being described as obsolete, the century-old technology may be equal and perhaps superior to today’s best voting systems, argues Bryan Pfaffenberger, a professor at the University of Virginia, who is currently writing a book on the history of lever machines. “I really think its an astonishing achievement,” he said. They have 28,000 moving parts and can be adapted to the myriad sorts of American elections (including, for example, picking multiple candidates for a school board). “They were designed so they could operate under punishing conditions and operate reliably,” he said, “and that they could be serviced by technicians of modest background.”

Of course, since they are so old, they often break down, and it is difficult to find new parts.

The lever machines were invented in 1888 in Britain and were used in New York City by 1892. They became widely adopted across the entire city by 1926 because they were seen as more resistant to tampering — a tremendous problem during 19th-century elections. The current outcry for a paper trail is a marked shift from when paper was seen vulnerable to human-perpetrated fraud. “There were so many meltdowns in the elections in the 1890s,” Professor Pfaffenberger said. “We started the 20th century with people preferring a machine that didn’t have a paper trail.”

“So many people are calling today for the paper ballot,” he said. “As a historian, when I hear that, I sort of cringe. It was because we were having so many problems with paper ballots that we moved to the lever in the first place. Although lever machines do not produce an independent audit trail, this is — as software engineers say — a feature, not a bug.”

Others also criticize the fixation on paper records. “Everyone is really hung up on the audit trail,” Ms. Novick said. “Counting paper after an election has never been allowed in New York State. For over 200 years, you cast it, you count it, you complete it on election night. That is a good system. That makes sense.”

New York, which was the cradle of the lever machine, has had a long relationship, even “love affair” with the voting apparatus, Professor Pfaffenberger said: “It’s quite long and deep.”

However, that affection did not run as deep in the rest of the country. By 1960, about 60 percent of the voters in the United States cast their ballots on the machines. (Problems in the 1960 presidential election in Chicago were largely limited to places that used paper ballots and not lever machines, Professor Pfaffenberger noted.)

But then punch cards systems came along at a fraction of the price — $100 versus $2,000 or $3,000 — and pushed out lever machines. The leading manufacturer, Automatic Voting Corporation, went bankrupt in 1983. But the vulnerabilities of punch cards were revealed in Florida during the 2000 election with butterfly ballots and hanging chads. “That was really a disaster,” Professor Pfaffenberger said.

The beauty of the lever machines, despite their jams, is that the voters’

choices are largely unambiguous. People cannot overvote (a problem with optical scan machines), and the machines do not vote-flip (a problem with touch screens).

“The lever won out and won out for a reason, because it is really transparent and deters theft,” Ms. Novick said.

Professor Pfaffenberger echoed, “During the great reign of the lever, it really performed as advertised.”

* Copyright 2009 The New York Times Company