Mourning Constitutional

September 01, 2009

By Matthew Ladner

September 17 is Constitution Day, marking the day 222 years ago in Philadelphia when the Constitution of the United States was signed. Legend has it that a woman asked Benjamin Franklin, as he was leaving the constitutional convention, what sort of government had been created. Franklin's reply: "A republic, if you can keep it."

A major justification for supporting a system of public schools has been the promotion of a general diffusion of civic knowledge necessary for a well-informed citizenry. America's founders, hoping to "secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity," knew that our system of ordered liberty would endure only if its citizens understood the nation's guiding principles. The endurance of American liberty, the founders believed, depends upon a broad knowledge of the nation's history and an understanding of its institutions.

Charles N. Quigley, writing for the Progressive Policy Institute, once explained the critical nature of civic knowledge: "From this nation's earliest days, leaders such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Adams recognized that even the well-designed institutions are not sufficient to maintain a free society. Ultimately, a vibrant democracy must rely on the knowledge, skill, and virtues of its citizens and their elected officials. Education that imparts that knowledge and skill and fosters those virtues is essential to the preservation and improvement of American constitutional democracy and civic life.

"The goal of education in civics and government is informed, responsible participation in political life by citizens committed to the fundamental values and principles of American constitutional democracy."1

For its part, the State of Oklahoma also lays out the goals of social studies education. According to the state's academic standards: "Oklahoma schools teach social studies in Kindergarten through Grade 12. ... However it is presented, social studies as a field of study incorporates many disciplines in an integrated fashion, and is designed to promote civic competence. Civic competence is the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required of students to be able to assume ‘the office of citizen,' as Thomas Jefferson called it.

"A social studies education encourages and enables each student to acquire a core of basic knowledge, an arsenal of useful skills, and a way of thinking drawn from many academic disciplines. Thus equipped, students are prepared to become informed, contributing, and participating citizens in this democratic republic, the United States of America."2

Some believe that traditional public schools have an advantage in promoting civic values. The rhetoric is familiar: public schools, available to everyone without charge, make an important statement about America's belief in the equality of opportunity. Richard Riley, Secretary of Education under President Clinton, noted that civic values are "conveyed not only through what is taught in the classroom, but by the very experience of attending [a public] school with a diverse mix of students."3

Of course, Riley was discussing the ideals of public education, not the actual practice, where strongly segregated housing patterns commonly produce highly segregated public schools, both in terms of income and of race and ethnicity. Nevertheless, this romantic vision of public education retains a firm hold on our thinking.

According to Oklahoma's most powerful labor union, the Oklahoma Education Association, "Public education provides individuals with the skills to be involved, informed, and engaged in our representative democracy." Research, however, indicates that public education does not provide individuals with those skills. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) administered a grade-level-appropriate civic knowledge exam to a nationally representative sample of 4th, 8th, and 12th graders in 2006. Only 25 percent of 4th graders, 24 percent of 8th graders, and 32 percent of 12th graders scored at the proficient level on the exam.

The percentage of students scoring "below basic" on civics was 27 percent, 30 percent, and 34 percent, respectively. In other words, at every grade level tested, there were more students failing the exam than demonstrating a solid mastery. Unfortunately, the NAEP does not provide state-by-state results for this exam.

Oklahoma High-School Students and the U.S. Citizenship Test

Last month OCPA commissioned a national research firm, Strategic Vision, to determine Oklahoma public high-school students' level of basic civic knowledge. The firm's surveys have been used by Time, Newsweek, and USA Today, and National Journal's "Hotline" has cited them as some of the most accurate in the country. The margin of error for this particular survey is plus/minus three percent.

Ten questions, chosen at random, were drawn from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) item bank, which consists of 100 questions given to candidates for United States citizenship. The longstanding practice has been for candidates for citizenship to take a test on 10 of these items.4 A minimum of six correct answers is required to pass. Recently, the USCIS had 6,000 citizenship applicants pilot a newer version of this test. The agency reported a 92.4 percent passing rate among citizenship applicants on the first try.5

Of course, immigrants have had an opportunity to study for the test-a distinct advantage-so we might not necessarily expect a 92 percent passing rate from Oklahoma's public high-school students.

On the other hand, most high-school students have the advantage of having lived in the United States their entire lives. Moreover, they have benefited from tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars being spent for their educations. Many immigrants seeking citizenship, meanwhile, often arrive penniless and must educate themselves on America's history and government.

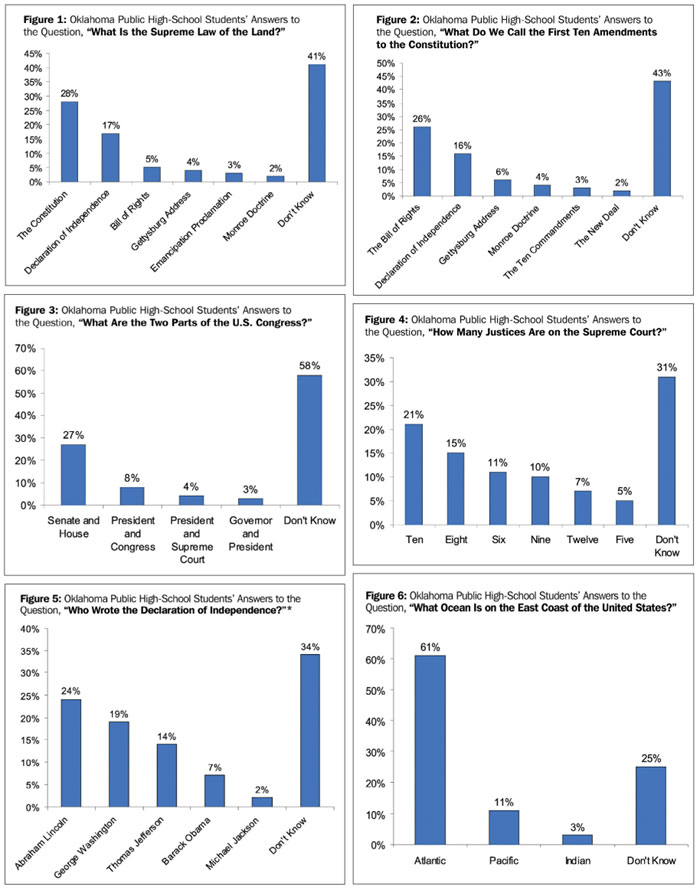

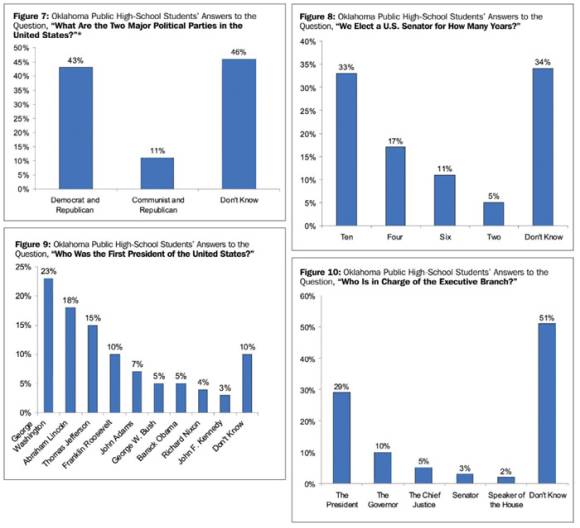

After seeing the questions for yourself, you the reader can judge whether a 92 percent passing rate is a reasonable expectation for Oklahoma's high-school students. Unfortunately, Oklahoma high-school students scored alarmingly low on the test, passing at a rate of only 2.8 percent. That is not a misprint.

Sadly, that result does not come as complete surprise. When the same survey was done recently in Arizona, only 3.5 percent of Arizona's high-school students passed the test. As the nation's largest newspaper, USA Today, editorialized: "[T]he Goldwater Institute, a non-profit research organization in Phoenix, found that just 3.5 percent of surveyed students could answer enough questions correctly to pass the citizenship test. Just 25 percent, for example, correctly identified Thomas Jefferson as the author of the Declaration of Independence.

"Other questions, all culled from the citizenship test, included: Who is in charge of the executive branch? (The president.) What is the supreme law of the land? (The Constitution.) How many justices are on the Supreme Court? (Nine.) The vast majority of students flubbed them all.

"Unfortunately, and unsurprisingly, this was no aberration. ..."6

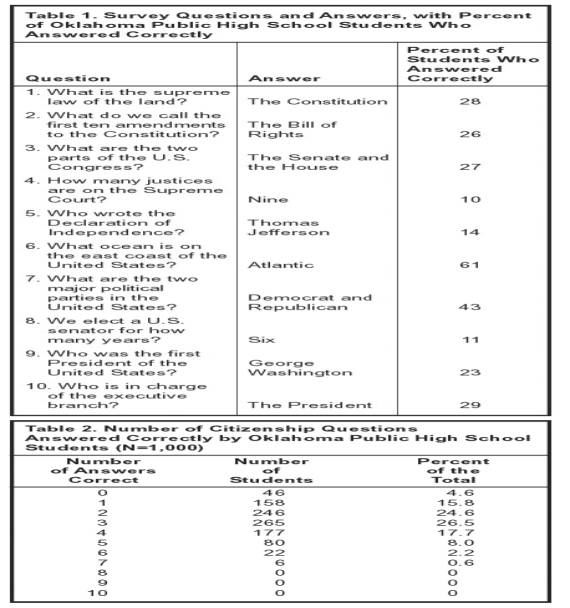

In Oklahoma, the telephone surveyors called a sample of 1,000 public high-school students and read the following statement: "On the next 10 questions, I will be asking you questions about American government and history. Give me your best answer, and it is permissible to respond ‘I don't know.'" The results are shown in Table 1.

In order to pass the citizenship test, an applicant must answer six of the 10 questions correctly. As you can see in Table 2, only 2.8 percent of Oklahoma high-school students attending public schools answered six or more questions correctly, and thus pass the citizenship test. Out of the sample of 1,000 students, only six students got seven questions correct, and none answered eight or more questions correctly.

Notice that the number of students answering either zero or one item correctly (204 students) is more than seven times larger than the number answering six or more items correctly (28 students). In short, Oklahoma's public high-school students have displayed a profound level of ignorance regarding American history, government, and geography.

Some readers may ask whether it's fair to administer the citizenship test to high-school students, since major sections of American history and government may be covered relatively late in high school, making the test unfair to younger students. However, Oklahoma's 8th grade social-studies standards read: "The focus of the course in United States History for Grade 8 is the American Revolution through the Civil War and Reconstruction era (1760-1877). However, for the Grade 8 criterion-referenced test over ‘History, Constitution and Government of the United States,' the time frame is 1760-1860, or from approximately George III's succession to the British throne to the election of Abraham Lincoln as president.

"The student will describe and analyze the major causes, key events, and important personalities of the American Revolution. He or she will examine in greater depth the factors, events, documents, significant individuals, and political ideas that led to the formation of the United States of America. These will be pursued through a chronological study of the early national period, westward expansion, and the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. Citizenship skills will focus upon the development and understanding of constitutional government in the United States. The student will continue to gain, develop, and put to use a variety of social studies skills."7

Under Oklahoma's 8th grade academic standards, students should learn all of the material needed to pass the citizenship test. Of course, they have had social studies in all the other grades as well, but 8th grade is important: we can be sure that a vast majority of students in Oklahoma public schools have taken this course. It does not appear, however, that the students have learned much from these courses.

Moreover, despite the fact that students take civics-related coursework in every grade, Oklahoma's 12th grade students performed only a tiny bit better on the survey than the overall average for all students. Again, Oklahoma students are taking the coursework, but don't appear to have learned much about American civics.

In considering the profoundly awful results of this survey, it is important to bear in mind that an open-answer format represents a much higher standard than a multiple-choice-format exam, even with high-quality exams such as the NAEP. After all, in a multiple-choice exam, the correct answer is sitting right in front of you.

For example, one of the questions in this survey is "Who was the first president of the United States?" If students are given four answers, and one of them is George Washington, they have a 25 percent chance of getting the correct answer even if they have no idea who the first president was. But in an open-answer format, you either know the correct answer or you don't. It is a higher standard, and it's the standard applied to applicants for U.S. citizenship.

Oklahoma Schools Are Failing at a Core Academic Mission

Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1789 that "Whenever the people are well-informed, they can be trusted with their own government." Years later he wrote, "Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day."

The promotion of knowledge of American government and history represents a core mission of Oklahoma's public schools. They are failing miserably to fulfill that mission.

The results of this survey are deeply troubling. Despite billions of taxpayer dollars and a set of academic standards that cover all of the material, Oklahoma high-schools students display an overwhelming ignorance of the institutions that undergird political freedom.

The students in this survey have taken multiple classes in social studies and history. If they had failed these courses, chances are good that they would not have made it into high school, and thus into the survey sample. Of course, the vast majority of these students never received a failing grade but instead were simply passed on to the next grade-whether they actually mastered any material or not.

What then to do about this situation? One is tempted to write yet another exhortation for schools to do a better job at teaching civics. Feel free to insert one here mentally, but given the catastrophic nature of these results, it rings hollow. One option would be to place more responsibility for learning about American government and civics with parents and students. My suggestion is straightforward. If the USCIS test is good enough for those seeking to become naturalized citizens of the United States, then it is also appropriate for American students seeking to become high-school graduates. In fact, in decades past, lawmakers in some states made passing a test similar to the one presented here a precondition to advancing to high school from middle school.

Given the proper motivation, people from all over the world pass a test similar to the one given here at a rate of 92 percent on their first try. Oklahoma lawmakers should require students to pass the USCIS citizenship exam in order to advance to high school.

To prevent problems such as teaching to the test, this exam should be administered by a third party. A third-party administration of an exam should not be difficult to arrange. Tests such as the Scholastic Aptitude Test, Advanced Placement exams, the ACT, and others are already administered by third parties for broadly similar reasons.

John Stuart Mill once observed that if government would simply require an education, they might save themselves the trouble of providing it (or in this case, unsuccessfully trying to provide it). If Oklahoma schools fail to get their civics house in order, it would be conceivable to remove the civic education function entirely from the public schools, and to have it done better than is currently the case. State lawmakers could make the passing of a civic knowledge exam a precondition for receiving a driver's license, and simply make the necessary study materials available online and at public libraries.

The costs of such a system would be a fraction of what Oklahoma taxpayers are currently spending, and it would likely prove much more effective. Ultimately, whether or not the public schools correct what has obviously become a gigantic failure, Oklahoma must see to it that children learn civics.8 Because Thomas Jefferson was right: "If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be."

Matthew Ladner (Ph.D., University of Houston) is vice president of research at the Goldwater Institute. His article "Demography Is Not Destiny" appeared in the November 2008 issue of Perspective.

Endnotes

1 Charles N. Quigley. 1999. "Education for Democracy." Available online at http://www.ppionline.org/ppi_ci.cfm?knlgAreaID=110&subsecID=181&contentID=1450

2 State of Oklahoma, Priority Academic Student Skills, page 219. Available online at http://sde.state.ok.us/Curriculum/PASS/Subject/socstud.pdf

3 Patrick Wolf. 2007. "Civics Exam." Article published in Education Next, Summer 2007. Available online at http://educationnext.org/civics-exam/

4 The question bank is available at http://usgovinfo.about.com/blinstst.htm

5 United States Citizenship and Immigrations Services. 2007. "USCIS Announces New Naturalization Test: October 2008 Start Date Gives Applicants One Year to Study." Press release available online at http://www.uscis.gov/sites/ocpathink/pressrelease/NatzTest_27sep07.pdf

6 USA Today. July 2, 2009. "Independence Day." Available online at http://blogs.usatoday.com/oped/2009/07/our-opinion-independence-day.html

7 State of Oklahoma, Priority Academic Student Skills, page 235. Available online at http://sde.state.ok.us/Curriculum/PASS/Subject/socstud.pdf

8 Portions of this text appeared previously in Matthew Ladner, 2009. Freedom from Responsibility: A Survey of Civic Knowledge Among Arizona High School Students. Publication of the Goldwater Institute, available online at http://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/article/3211